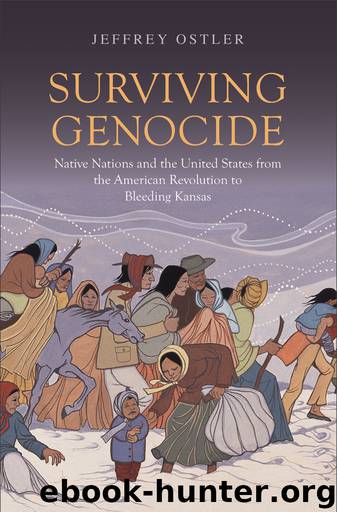

Surviving Genocide by Jeffrey Ostler;

Author:Jeffrey Ostler; [Ostler, Jeffrey]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2019-06-16T16:00:00+00:00

Fig. 35. First and Second Seminole wars

THE SECOND SEMINOLE WAR

With a removal treaty in hand, U.S. officials moved to implement it. In October 1834 government agent Wiley Thompson met with Seminoles at Fort King, in the northern part of the Seminole reservation in central Florida. When Thompson ordered the Seminoles to prepare for removal, they all refused. An emerging leader named Osceola had migrated as a child with Red Stick Creeks. Now close to thirty years old, he urged his people to obey the “Great Spirit” by not departing “from the lands which we live on, our homes, and the graves of our fathers.” Other leaders objected that they had never agreed to the 1832 treaty. Micanopy, for example, contended that “I did not touch the pen; I only reached over and pointed to it.” Thompson accused Micanopy of lying, but Charley Emathla countered by saying, “At Payne’s Landing the white people forced us into a treaty” and pointing out that unlike Thompson, “I was there.” An unmoved Thompson told the Seminoles that “you must go; and if not willing, you will be compelled to go.”56

Soon after, President Jackson authorized an increase in troops stationed at Fort King. Should the Seminoles refuse the Great Father’s wish that they vacate their homes, Jackson told them (through Thompson), “I have then directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force.” Rather than submit to this threat, Seminoles decided to fight. On December 28, 1835, a force of 180 Seminoles led by Micanopy, Jumper, Hulbutta Harjo (Alligator), and the Black Seminole Abraham attacked a U.S. military detachment marching from Tampa Bay to reinforce Fort King, killing all 110, including its commander, Major Francis Dade. The same day, Osceola and other Seminoles raided Fort King and killed Agent Thompson. Not since the western confederacy’s destruction of St. Clair’s army in 1791 had Indians killed as many Americans.57

These attacks were not rash acts taken on the spur of the moment. The Seminoles’ decision to go to war was as carefully calculated as the Cherokees’ decision to take Georgia to court. Why were Seminoles, more than the other southeastern nations, willing to fight? Like all other Indian nations, they loved their land. One of their chiefs, known in the sources by his English name, John Hicks, explained it this way: “Here our navel strings were first cut, and the blood from them sunk into the earth and made the country dear to us.” But Seminoles were a relatively small nation. Including Black Seminoles, they numbered between 5,000 and 6,000, only a quarter the size of the Creeks or the Cherokees. How could they hope to prevail against the United States?58 One possible explanation is that Seminoles had no choice. Black Seminoles, in particular, felt their only alternative was to fight to preserve their freedom. It was either war or a return to former chains somewhere in the South or enslavement by wealthy Creeks. But, although Black Seminoles had influence, they did not control Seminole decisionmaking.59 Why

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African-American Studies | Asian American Studies |

| Disabled | Ethnic Studies |

| Hispanic American Studies | LGBT |

| Minority Studies | Native American Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32022)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31436)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31380)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(30641)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18605)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(14592)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(13717)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13665)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12886)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(12813)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(12785)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(11331)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8860)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(8664)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7125)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6852)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6284)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6255)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5801)